Healthy hydrocolloids: Designing foods with a healthier structure

The ability to modify the micro- and macro-structure of food products using hydrocolloid science offers the food industry a plethora of opportunities to make healthier and better tasting foods, say experts.

Hydrocolloids form the basis and delivery system for a big chunk of a food’s nutrient energy, in addition to being key in the make-up of a food’s overall structure. As a result, they play a major role in defining both the sensory and nutritional qualities of a product, according to many experts.

“A case can be made that hydrocolloids are the single most important class of food component as far as behaviour in the digestive tract and consequent nutritional and health outcomes are concerned,” suggests Professor Mike Gidley from the University of Queensland, Australia.

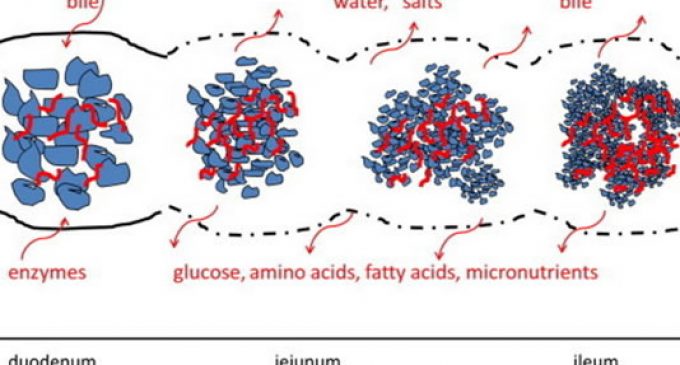

Indeed, the way in which any hydrocolloid-structured food product breaks down during digestion determines many nutritional properties that are controlled by factors such as the rate of passage, nutrient absorption, and fermentation.

Tailoring nutrition

According to a recent review by Gidley (found here ), there is often a parallel between the functionality of the plant-based foods which the human digestive tract evolved to digest and the use of extracted hydrocolloids in modern food structuring technology.

“Processed foods with nutritional and potential health benefits that have been developed more recently often mirror the functionality of pre-agricultural foods with additional advantages of convenience and diverse sensory properties.”

Gidley suggests that improved utilisation of hydrocolloids when designing and reformulating foods can help industry to create foods that are intrinsically healthier than other products on the market.

Writing in Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science , he observed that the ability to design and manipulate hydrocolloids to alter the way in which they are broken down by the digestive system offers the food industry “a major opportunity to tailor nutritional value and provide potential health benefits through control of gastric emptying and ileal brake mechanisms (satiety and potentially obesity), glycaemic response (diabetes), plasma cholesterol levels (cardiovascular disease), and carbohydrate fermentation throughout the large intestine (colon cancer).”

In addition, he suggests that many nutrients may bind directly to hydrocolloid structures – thus offering solutions for nutrient delivery that do not involve encapsulation technologies.

“This phenomenon is now recognised as being important for a range of phytonutrients, particularly phenolic compounds, which appear to be bound sufficiently strongly to plant cell walls that they escape solubilisation and uptake in the stomach and small intestine,” said Gidley.

“By escaping digestion in the stomach and small intestine, phenolic compounds bound to plant cell wall hydrocolloids become a potential substrate for fermentation in the large intestine, which may influence microbial ecology and which may cause metabolic transformation of phenolic compounds prior to potential absorption,” he suggested.

Lower salt and sugar

In addition to manipulating the delivery of foods and essential nutrients to the digestive system for health benefits, there is also a big opportunity to reduce the levels of salt and sugar in processed foods by manipulating hydrocolloids and food microstructure.

Indeed, a review paper led by Fred van de Velde of NIZO Food Research (found here ) suggests that by understanding the role of microstructure and oral processing in sensory perception and appreciating the underlying mechanisms by which they function, researchers and industry can apply these principles to the design and development of food products that support a healthy lifestyle.

“There is a demand for food products with reduced contents of sugar, salt and fat,” explained van de Velde and his colleagues.

“Understanding the relationships between food microstructure, texture and sensory perception, allows us the design of foods with specific functionalities,” he said, noting that there are many new approaches that aim to reduce sugar and salt by redesigning the microstructure and texture of semi-solid foods.

Indeed, he noted that ‘significant’ reductions of salt and sugar are possible in soft- and semi-solid model foods by increasing the serum release: “While this approach demonstrates how the microstructure of a semi-solid model food can be designed to maximise the release of tastants, the approach is limited to sugar and salt reduction in foods for which serum release or juiciness is a favourable sensory property, such as processed meat products.”